ASTROPHYSICS

Supersonic Turbulence in Galaxies

Principal Investigator:

Prof. Dr. Marcus Brüggen

Affiliation:

University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Local Project ID:

nonequioutflows and SHOCKCLOUD

HPC Platform used:

JUWELS CPU and JUWELS BOOSTER at JSC

Date published:

The simulations were run using the highly scalable hydrodynamics code ATHENA-PK on GPU nodes of the JUWELS BOOSTER system, using between 16 and 48 nodes.

Turbulence is a ubiquitous phenomenon that affects everything ranging from blood flow in our arteries, via aircraft to processes that form stars such as our Sun. In particular, turbulence that moves faster than the speed of sound, so-called supersonic turbulence, is important in many astrophysical settings, for example in giant molecular clouds that are the birth places of stars and that are scattered throughout galaxies. However, many properties of supersonic turbulence are poorly understood.

In a new study enabled by resources provided by the supercomputing centre in Jülich, scientists have created simulations to explore how turbulence interacts with the density of the cloud. Lumps, or pockets of density, are the places where new stars will be born. Our Sun, for example, formed 4.6 billion years ago in a lumpy portion of a cloud that collapsed. We know that the main process that determines when and how quickly stars are made is turbulence, because it gives rise to the structures that create stars. This study investigates how those structures are formed.

Giant molecular clouds are full of random, turbulent motions, which are caused by gravity, stirring by the galactic arms and winds, jets, and explosions from young stars. This turbulence is so strong that it creates shocks that drive the density changes in the cloud. Each shock leads to an enhancement in the gas density and a random succession of such enhancements leads to a density distribution that follows a normal distribution of the logarithm of the density. However, it was not understood what sets the width of this distribution. Given that stars form only on the extreme end of this distribution, i.e. at the highest densities, this study addresses a very fundamental question.

The simulations run on GPU nodes of the JUWELS BOOSTER used so-called tracer particles to that travel along with the material. As the particles travel, they record the density of the part of the cloud they encounter, building up a history of how pockets of density change over time. The researchers simulated boxes of turbulent gas in which the gas is continuously stirred, varying the Mach number and the way the gas is stirred.

The team found that the speeding up and slowing down of shocks plays an essential role in setting the density distribution in turbulent gas. Shocks slow down as they go into high-density gas and speed up as they go into low-density gas. This is akin to how an ocean wave strengthens when it hits shallow water by the shore. When a particle hits a shock, the area around it becomes more dense. But because shocks slow down in dense regions, once lumps become dense enough, the turbulent motions cannot make them any denser. These lumpiest high-density regions are where stars are most likely to form.

While other studies have explored molecular cloud density structures, this simulation allows scientists to see how those structures form over time. Moreover, it was found that it matters how frequently the gas is stirred to create the turbulence. In galaxies this turbulence is created by explosions of stars, so-called supernova explosions. Thanks to this work, we can identify the conditions under which the ensuing supersonic turbulence created the required dense pockets of gas that then give birth to stars, and ultimately life.

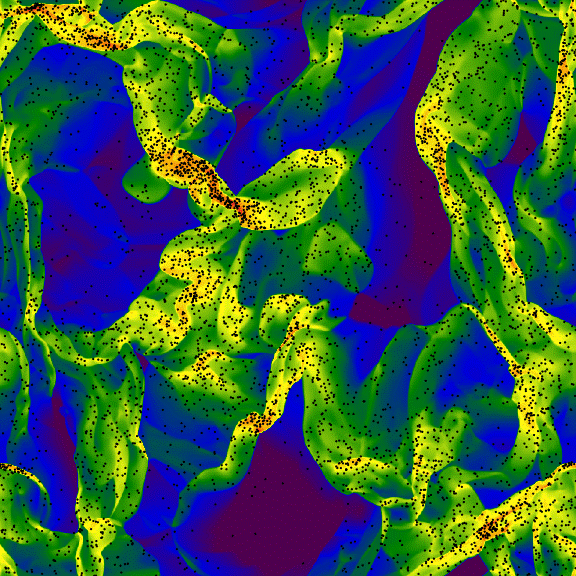

Image: NASA/E. Scannapieco et al. (2024)

This image shows part of a simulation of a molecular cloud. The colors represent density, with dark blue indicating the least dense regions and red indicating the densest regions. Tracer particles, represented by black dots, traverse the simulated cloud. By examining how they interact with shocks and pockets of density, scientists can better understand the structures in molecular clouds that lead to star formation.