ENVIRONMENT AND ENERGY

Direct Numerical Simulation of Turbulent Mixing in the Planetary Boundary Layer

Principal Investigator:

Juan Pedro Mellado

Affiliation:

Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg

Local Project ID:

hhh07

HPC Platform used:

JUQUEEN of JSC

Date published:

Whenever we travel by plane, we often experience that the flight becomes bumpy quite suddenly during the descent. This phenomenon causes not only discomfort to the passengers, but also a few headaches to climate scientists, whose models depend critically on properties associated with this phenomenon.

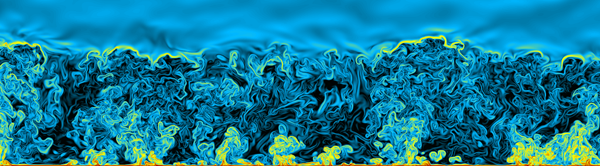

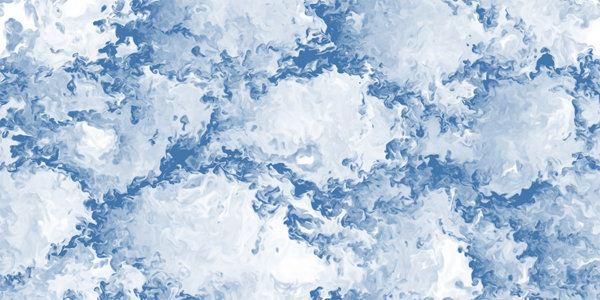

The sudden agitation indicates that we are abandoning the relatively calm free troposphere and we are entering into the planetary boundary layer, filled with turbulent motions (see Fig. 1). Within this transition region, air from the free troposphere above is mixed into the planetary boundary layer, and the local thermodynamic conditions change accordingly. Cloud processes, like the cooling caused by radiation or by the evaporation of droplets, may amplify the relevance of this local mixing to the extent that small-scale turbulence becomes one of the dominant mechanisms in the evolution of the planetary boundary layer and the clouds themselves (see Fig. 2).

Figure 1: Vertical cross-section showing the turbulent boundary layer, filled with chaotic motions of many different scales, and the upper troposphere, characterized by gentle undulations. The colour indicates the magnitude of the local variation of the density field, increasing from black to yellow to red. Simulation performed at the Jülich Supercomputing Centre using 5120 × 5120 × 840 grid points. Copyright: © Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg

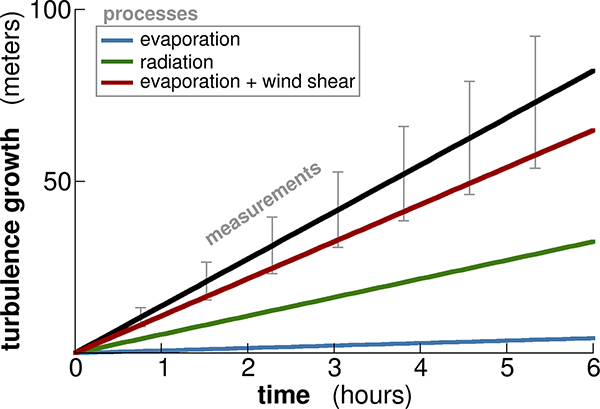

Advances in super-computing allows nowadays to simulate directly – without intermediate turbulence models – the details of the turbulent motions inside of the planetary boundary layer. We can cover a range of scales of several orders of magnitude, from the large, organized ascending thermals to the small, apparently random vortices. Also, computers allow us to solve accurately idealized problems in which we can switch on and off different cloud processes selectively, like evaporative and radiative cooling, learning thereby how important these processes really are (see Fig.3).

Figure 2: Horizontal cross-section inside a cloud deck at the top of the planetary boundary layer. The normalized liquid water content is shown varying from blue (dry air, moving downward) to white (cloudy air protruding out of the page, towards the reader). Simulation performed at the Jülich Supercomputing Centre using 3072 × 3072 × 2216 grid points. Copyright: © Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg

As an example of the new findings that this line of research is providing, we have learned that the transition region at the top of the planetary boundary layer, about 100 meters high, comprises in reality two different sub-layers. The upper sub-layer, characterized by the crests or domes observed in Fig. 1 at the top of the turbulent region, is where the troposphere opposes the advance of turbulence most strongly. This region is characterized by local properties different from those describing the rest of the planetary boundary layer. The lower sub-layer acts as a transition towards the underlying well-mixed central region of the planetary boundary layer.

An extension of this analysis considers the effect of surface heterogeneity, like the alternation of ice-covered and ice-free regions in the ocean, which modifies the general structure of the planetary boundary layer and the way it grows into the troposphere. Another line of research of this project investigates the turbulence intermittency and collapse that appears, for instance, in the nocturnal boundary layer or in arctic regions, as the surface cools down with respect to the troposphere.

Figure 3: Turbulence growth into the upper troposphere due to different cloud-top processes inside the transition region between the turbulent boundary layer and the troposphere (see Fig. 2). Evaporation alone (blue line) cannot explain the measurements (black line), whereas radiation and in particular wind shear can, indicating that these last two processes are more important in the turbulence growth. Copyright: © Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg

Scientific Contact:

Dr. Juan Pedro Mellado

Max Planck Institute for Meteorology

Bundesstr. 53, D-20146 Hamburg/Germany

Turbulent Mixing Processes in the Earth System - Group Website